The officially stated rate of U.S. unemployment in April 2020 was 14.7%, the highest since the Great Depression, when the data were not as rigorously tabulated compared to these days. Regardless of whether the 14.7% number is exactly correct (it isn’t), it is still a high number. And May’s number may be higher still when it gets announced on June 5.

That is a horrible development for our country, because our GDP misses out on the economic contributions of those who are not working. And the state and federal unemployment benefits drive up deficits, crowding out other expenditures, while the tax revenues resulting from employment are reduced. Plus, the individual workers see their own personal wealth drop, in some cases spiraling further into debt. Hopefully this time we can have the fastest ever rebound in all of economic history.

High unemployment is bad in so many ways, but it is very bullish for stock prices. Note that “bullish” is not the same thing as “good”. A bull market is great for those who are already invested, but bad for those who would have liked to have bought at the lower prices. It is important for us to separate those concepts in our minds. Something can be bad while still being bullish.

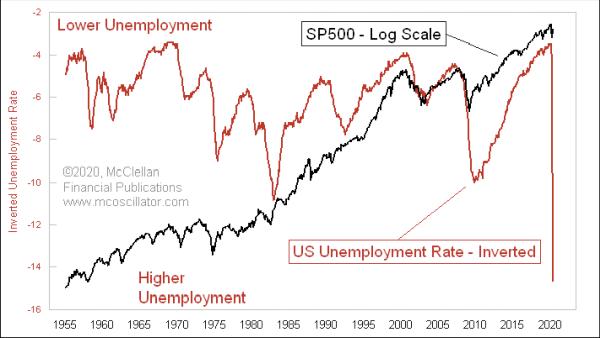

This week’s chart compares the inverted plot of the U.S. unemployment rate (U-3) to the S&P 500. Inverting the unemployment rate in this manner helps us to better see the correlation between the two.

The first point to notice in the chart is that the S&P 500 typically bottoms about 4-to-12 months ahead of the worst point for the unemployment rate. After an economic depression starts, stock investors become optimistic again faster than hiring managers, it seems.

The second point, and perhaps the more important point, is that instances of high unemployment rates tend to be followed by several months of rising stock prices. This does not make sense in conventional economic terms. After all, higher unemployment means weaker GDP and lower company earnings, the latter being what is supposedly the most important factor for stock prices.

But high unemployment also tends to bring a much more accommodative Federal reserve. When the COVID Crash unfolded, the Fed dropped its Fed Funds target rate down all the way to 0-0.25%. The Fed also ramped up QE4 at the fastest rate of QE that it has ever engaged in. This has been tremendously stimulative to the stock market’s rebound, and the Fed is not likely to back away from this stimulus until it is clear to the decision makers that the economy and unemployment have turned a corner. In the meantime, those stimulative efforts will continue to help boost stock prices higher.