The following is an excerpt from Mark Tobak MD’s book, titled, “Anyone Can Be Rich!: A Psychiatrist Provides the Mental Tools to Build Your Wealth“, discussing the force of compound interest.

Q2 2020 hedge fund letters, conferences and more

Chapter 6 – The Power of the Force: Compounding

In Star Wars: A New Hope, Obi-Wan Kenobi introduces Luke Skywalker to the Force: “An energy field created by all living things. It surrounds us, penetrates us, and binds the galaxy together.” It may surprise you to learn there really is a force in nature as powerful as the Force in Star Wars. It is no fantasy. Like the Star Wars Force, it has infinite and unstoppable power. Like the Star Wars Force, it has a light and a dark side. The light side enriches and ennobles those who embrace it. Pity the poor souls who, like Darth Vader, are seduced by the dark side of this real-life force.

The force is called “compound interest.” It is not included in the toolkit of common sense. It requires book smarts to understand. If you glean but a single idea from this book, it should be this quote attributed to Albert Einstein, the reallife model for Yoda in Star Wars: “Compound interest is the most powerful force in the Universe. The Eighth Wonder of the World. He who understands it, earns it. He who doesn’t, pays it.”

Compound interest is one idea from Einstein that is comparatively easy to understand. The other is the thought experiment that we will meet again later in this chapter.

Let’s begin with basics. There is simple interest. You lend $100.00—that’s your principal—at 5 percent interest. The first year you receive $5.00 interest back on your principal, and your account balance is now $105.00. The second year you get another fiver, and your account balance is $110.00. Each year, another $5.00. Quite simple, and it is called “simple interest.” Because there is no interest on the interest, only on the principal. Well, who cares about interest on interest? It must be chump change. That is true, at first. But read on.

Compound interest is simple interest plus the interest on the simple interest, compounded once, twice, or four times a year. I’ll keep it simple and do a calculation for once per year. So lending $100.00 at compound interest yields the same $105.00 in year one.

But year two is not $110.00. It is $110.25 with a mere $0.25 in interest on the $5.00 you received as simple interest. Chump change for sure. But in ten years’ time when simple interest has yielded $150.00, compound interest has grown to $162.89. In twenty years when simple has yielded $200.00, compound interest has grown to $265.33. In fifty years simple interest yields $350.00, but compound interest now displays the power of the force: $1,146.74. Do you begin to get the point? If you have a higher interest rate, compound interest grows bigger and faster. At 10 percent, the rough historical return of the S&P 500, the thirty-year figure is $1,744.94 and the fifty-year figure is $11,739.09. With a long enough time frame, more frequent compounding, and regular contributions to principal, in the words of Leo Bloom in The Producers,48 “A man could make a fortune!” Except unlike Max and Leo in The Producers, it’s perfectly legal and risk free, involves no effort, and harms no one. It’s what Charlie Munger likes to call “sit on your ass investing.”

Let’s take a real-life example. A twenty-five-year-old earns $50,000 per year and vows to save $5,000 per year in a tax-deferred retirement account over a forty year working life. The person seeks only a 5 percent return through very conservative investing—for example, preferred shares of stable corporations. No growth, just reinvested dividends. The future value of the investments is $674,164 at retirement. Make that return rate 10 percent, the rough historical return of the S&P 500, and it grows to $2,660,555. Amp up the savings with anticipated raises and perks to $10,000 per year: $5,321,110. Work to age seventy-five, and it balloons to $13,976,902. You can use one of the online compound-interest calculators and prove it to yourself. That’s how I was taught organic chemistry by the late Professor Wolff at Columbia University: do it yourself, and prove it to yourself.

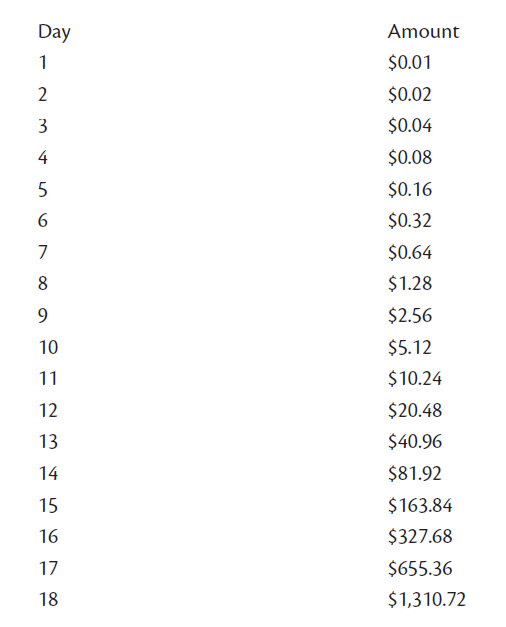

Perhaps the best illustration of the counterintuitive nature of compound interest is the following trick question. Which would you rather have: one million dollars right now or a penny doubled every day for a month? Common sense tells you to take the million and run. But put on your thinking cap and run it through the calculator for thirty or thirty-one days of the month:

Over five or ten times as much as the million dollars, depending upon whether it’s a thirty-day or a thirty-one-day month! No chump change here. With a long enough runway, you take off for the wild blue yonder.

That’s the force of compound interest!

You can see that compound interest has three important characteristics:

- It is not part of the commonsense toolkit, and it is not intuitive.

- It grows slowly but inevitably, faster and bigger with a higher rate or frequency and a longer term.

- It flies into orbit at the end of a long, slow climb.

Applying this to daily life, you can draw three important conclusions:

- If I compound money all my life in untaxed retirement accounts, I will grow rich as I mature.

- If I spend my money now instead of compounding it, I will destroy my future wealth.

- If I borrow money at interest, I might never be able to pay it off, because the compound interest on the debt will grow and keep me poor all my life.

Yes, number three is a killer! Debt at interest is the dark side of the force of compounding. Going to the dark side of compound interest is buying on credit, instead of waiting and saving for what you want or not buying at all. Remember how the thrill of gambling winnings and found money was revealed to be an addictive and dangerous drug in chapter 1. Similarly, the excitement of buying on credit can be addictive and thrilling in much the same way. All addictions corrupt and destroy. The dark side of the compounding force can seduce and destroy you and your family. That’s why Warren Buffett shuns debt. It has ruined many of his fellow financial titans and many a workaday neighbor as well.

The mass public does not understand the force of compound interest. Common sense does not include the force of compound interest. But credit-card companies, loan companies, brokers, and money managers understand the force of compound interest very well. More importantly, they understand that the public does not. That is why your junk mail is filled with solicitations for credit cards, even in the names of your beloved dead relatives, previous owners and tenants, your dogs, and your cats. Credit cards bear high interest rates and compound relentlessly with late fees and penalties galore. They are money machines for the credit-card companies, who are the loan sharks of our age even as they pretend to be our benefactors and friends. Brokers and money managers who take a 1 percent or 2 percent share of your account per year know full well how it will diminish your future wealth and what it will do for their present-day income and their compounded future wealth.

Charlie Munger recommends getting rich slowly.50 Why? Because windfall money often destroys people. Read about lottery winners. The stories are online. They are often bankrupt in a year or two: divorced, unemployed, swindled, and depressed. Found money corrupts because it was never earned. We value only what we earn. If you earn money and compound it slowly over a lifetime, not only will you have independence and comfort in old age and the ability to improve the course of your children’s lives, but you will also have pride in your accomplishment, in what you have built.

What’s the other reason Charlie Munger recommends getting rich slowly? It’s a safer bet! If you invest and compound over a lifetime, you are almost certain to get rich. Absent disaster—atomic war, meteor strike, famine, long-term depression, and chaos—it is a near-mathematical certainty.

Let’s use a cinematic example everyone knows and loves: Marilyn Monroe. Despite a tormented life and horrible death, she remains a beloved, perhaps the most beloved, star of the silver screen. In two of her most famous films, Gentlemen Prefer Blondes51 and Some Like It Hot,52 she portrays, for better or worse, a gold digger—a beautiful young woman who seeks a wealthy husband. We do not disdain her for it. As with anyone beloved, we celebrate her virtues and ignore her faults. In any case, who wouldn’t be blessed to be in the company of Marilyn Monroe?

What is the single most important thing Marilyn, as Lorelei Lee and Sugar Kane, discovers in the course of the arc of each film?

Rich men are usually very old!

Yes, their wealth has been built over a lifetime of careful accumulation and compounding. And in each film she disdains the older man in favor of the young scion of the family (one real, one a pretender, Tony Curtis), so she can enjoy young love and old money at the same time. (Spoiler alert: When Tony turns out to be a phony millionaire, she still loves him. No gold digger after all.)

But the force of compound interest is not limited to finance. It is a force in all of life, in the expansion of populations, and in the wealth of nations. Trust compounds. Friendship compounds. Faith compounds. Honor compounds. Love compounds. It results in what Charlie Munger likes to call “a web of deserved trust.” It is a force in the building of a business or a law, medical, or accounting practice. It can be a source of great joy, as Charlie Munger says, “There is huge pleasure in life to be obtained from getting deserved trust.”53 Returning again to the movies, the best cinematic example of compounded virtue and deserved trust is Frank Capra’s It’s a Wonderful Life.54

Let’s take a good long look at the life of George Bailey, portrayed by James Stewart in the 1946 Liberty Films picture that has become the ultimate holiday evergreen—so widely viewed it needs no spoiler alerts.

In 1919 in the mythical New York town of Bedford Falls, George Bailey, a boy of twelve, risks his life to save his kid brother, Harry, from drowning. His left ear becomes infected in the plunge, and he loses his hearing in that ear during the pre-antibiotic era. Then he suffers a beating—to that very left ear—to save another child’s life and his pharmacist-employer’s livelihood and profession. It is a fearful thing to see a drunken, grieving adult beat an innocent, bleeding child. (New viewers learn early on that this story will not be standard Hollywood fare.) When Mr. Gower, the pharmacist, realizes that George has saved both him and the child, he hugs, cries, and thanks him, and we witness one of the tenderest scenes in the history of film. George learns to employ Charlie Munger’s fundamental algorithm of life: “Repeat what works!”55 For George, what works is kindness, fairness, generosity, sacrifice, and goodness. He has been taught it by his parents, Peter and “Ma” Bailey—she is never named—who exemplify it. Careful viewers will spot an obscure sign behind the adult George Bailey’s desk: “All you can take with you is that which you have given away.”

Yet young George has his own dreams: he wants a million dollars, to get away from Bedford Falls, to travel, to “build modern cities,” and to find adventure, excitement, and, implicitly, sexual gratification (“a couple of harems, and maybe three or four wives!”). But as a grown man, George never does anything he wants, always putting the needs of others before his own. He passes up steamy sex with Violet, the ever-available town hottie who George knows needs protection from herself. He gives up college, travel, and wealth to save his ne’er-do-well Uncle Billy, who can’t run the Bailey Brothers Building & Loan Association alone after Peter Bailey dies. He sends his brother, Harry, to college and unwillingly nurtures and grows the Building & Loan to help poor townsfolk buy homes in his Bailey Park. He sacrifices for his wife, Mary, and the four children he was never sure he wanted, all of which keeps him from ever realizing his personal hopes and dreams of pleasure and wealth.

But instead of success, for all his sacrifice, George is brought to ruin by that same Uncle Billy when the befuddled near-alcoholic loses $8,000 of the company’s money (over $100,000 in today’s dollars) taunting old man Potter, the movie’s greedy villain and Peter Bailey’s nemesis, by dropping it in Potter’s lap, folded in a newspaper announcing Harry Bailey’s triumphant return from the war—Harry Bailey, the hero that George could have been if he’d never saved his brother and become “4-F on account of his ear.”

It can only get worse. George lends money to destitute Violet, who kisses him in gratitude. The lipstick smear sets off an ugly rumor of infidelity and, perhaps, a kept woman. When George begs Potter for a loan on his $15,000 life-insurance policy to replace the $8,000 Potter now holds, Potter taunts him with the rumor and calls the district attorney, telling George he is worth more dead than alive. George concludes that his only way out is to take Potter’s suggestion, kill himself, and, in dying, save the Building & Loan and his soon-to-be destitute family. Even in choosing death, George is dying for others.

How can the plot now save George from an ignominious end?

Deus ex machina! A watchful heaven sends an angel, Clarence, a simple but persistent clockmaker, to apply his clockmaker’s logic to save George and everyone else. The angel intervenes, most importantly by jumping into the river, obliging George to save him rather than drown himself in his planned suicide. “I jumped in the river to save you!” says Clarence. But George regrets being saved. He can see no way out of his dilemma. George wishes he were never born.

An idea is born instead. Clarence applies a simple rule of Carl Jacobi’s nineteenth-century mathematics to George’s world to save George and everyone else: inversion, a rule that Charlie Munger recommends to anyone with a seemingly insoluble problem. Look at the problem upside down or backward and see it afresh.56

Clarence also creates an Einsteinian thought experiment–given cinematic expression in a simulation that remains one of the most powerful sequences in cinema history. Clarence, with heavenly assistance, simulates for George the world as it would have been without him, the George-free decompounded world of Pottersville. “You’ve been given a great gift, George—the chance to see what the world would be like without you.”

It is the world of Bedford Falls without all the compounded love, faith, care, and trust that George has brought to it. It is a horrid, decadent, self-indulgent, amoral, inebriated, childless hell that, when compared to an $8,000 debt, a scandal, and a prison term, makes George’s current troubles seem like a day at the beach. In the nightmare Georgeless world of Pottersville, unwound from George’s compounded love and devotion, Harry is dead, drowned at the age of ten. Dead as well are the soldiers Harry saved in the war. Mr. Gower the druggist is the town drunk who killed a kid. Uncle Billy has been in the insane asylum since the Building & Loan went bust after George’s father died. Without George to support her, Ma Bailey runs a two-bit boarding house, an embittered widow. Violet is a dime-a-dance girl or worse, rolling sailors and by inference dallying with Potter, who now owns and operates the corrupted Pottersville filled with nightclubs, strip joints, poolrooms, and bars. George’s children were never born, for in the selfishness of his wish to have his life erased, he has, in effect, aborted them. The old Granville house that Mary made a home is in shambles, and poor Mary, whom we know from the beginning of the movie could love only George, is a guarded and fearful old maid (this is 1945) and the town librarian, if anyone in Pottersville reads.

The inverse thought experiment, realized so dramatically on the screen, catapults George into a new reality. His life has meaning because of what he has done for others. George experiences firsthand a mounting cascade of devastating losses (recall the discussion of loss in chapter 4), the hole left without him and its compounded consequences. George begs Clarence, “Get me back. I don’t care what happens to me. Get me back to my wife and kids.” And by renewed heavenly intervention, Clarence brings George back to face his fate.

But we are not done with the effects of compounding. The compounded love and devotion that George has given to others now yields the bounty that lies at the end of a compounded life well led, the seamless web of deserved trust.57 His friends and neighbors rush to save him: he reaps what he has sown. Compounded love is repaid with love. The townspeople do not believe Potter’s lies. They know George, and they know Potter. Their compounded reputations have preceded them. Friends, relatives, neighbors, depositors, and borrowers all pony up the $8,000 and more to save George from ruin and prison.

They don’t revile him; they celebrate him. Even his wealthy childhood rival for Mary’s hand, “Hee-Haw” Sam Wainwright, sends a telegram authorizing release of $25,000 (over $300,000 in today’s money) to protect George from whatever trouble he is in, no questions asked. The seamless web of deserved trust borne of compounded virtue has saved our George.

We exit the movie confirmed in what we thought we knew but were never quite sure of—that virtue and goodness triumph and that a just and loving God watches over us all. The film is based upon a short story by Philip Van Doren Stern that could not find a publisher and so was sent as a Christmas card to Stern’s friends and relatives and entitled—what else?—“The Greatest Gift.”

But for our purposes it is ever important to remember, it is not divine intervention that saves George and Bedford Falls. Clarence is only a messenger, a Diogenes who holds up a lamp for George and the viewer to behold the compounded virtue of a life well led. Alternately, we see compounded sin and folly when, as Edmund Burke said, “good men do nothing” and “evil triumph[s].”58

Summing up, what have we learned in this chapter?

- Compound interest is the true power of the force.

- Everything compounds: investments, goodness, and virtue as well as debt, sin, and folly.

- The light side can let you grow virtuous and rich, and the dark side can drive you to become addicted, selfish, and poor.

- Barring tragedy, anyone can engage the light side, grow rich, and lead a wonderful life.

The post The Power of the Force: Compounding appeared first on ValueWalk.